Archive for June, 2019

Beyond the Milky Way | Update 23

Jun 25th

June 28: Update 23.0.1 is a small patch to fix an issue with tidal heating.

Run Steam to download Update 23, or buy Universe Sandbox via our website or the Steam Store.

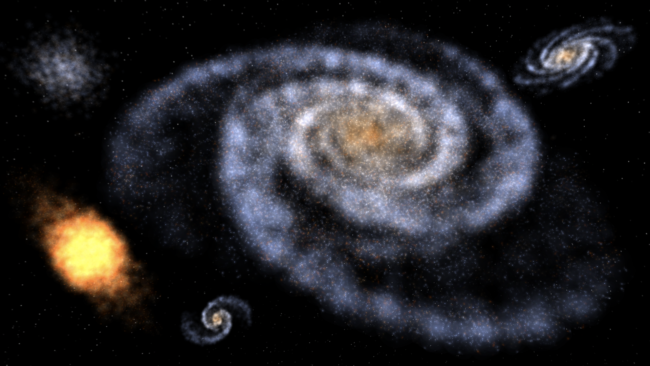

This update adds brand new galaxies that are much more interactive, accurate, and varied, making it easier than ever to create and customize on a galactic scale.

Three Types of Galaxies

Use the Add tool to procedurally generate a Spiral, Elliptical, or Irregular galaxy and add it to any simulation. Or select from galaxies like the Milky Way, Andromeda, or IC 1101, one of the largest known galaxies.

Accurate, Data-Driven Motion & Visuals

The motion and shape of the galaxy are now determined by its type and properties. You’ll also see red-yellow elliptical galaxies where the stars are older and bluer spiral arms where the stars are younger and hotter.

Full Customization

Adjust standard properties like mass and radius plus unique galaxy properties like the number of spiral arms and amounts of dust and gas.

Learn more about the new galaxies:

Home > Tutorials > 11 – Exploring New Galaxies

Or get started with the included galaxy simulations:

Home > Open > Galaxies tab

Check our a full list of What’s New in Update 23

Follow @universesandbox

Surface Grids & Lasers | Dev Update #6

Jun 23rd

Here’s our round six update on the development status of Surface Grids and Lasers. If you haven’t seen them yet, check out Dev Updates #1, #2, #3, #4, and #5.

This will be a smaller update than usual because we’re focusing our efforts on the last sprint for the new galaxies we’ve been working on. We hope you won’t have to wait long for their official release, but if you’re feeling impatient, you can check them out by opting into the experimental version.

A primer on Surface Grids for anyone not familiar:

It’s a feature we’re developing for Universe Sandbox that makes it possible to simulate values locally across the surface of an object. In effect, it allows for more detailed and accurate surface simulation and more dynamic and interactive surface visuals. It also makes it possible to add tools like the laser, which is essentially just a fun way of heating up localized areas of a surface.

Keep in mind this is a development log for a work-in-progress feature. Anything discussed or shown may not be representative of the final release state of Surface Grids.

Set Phases to Accurate

Our last dev update focused on the upcoming galaxies, but at the end we mentioned how Jenn, astrophysicist and Universe Sandbox developer, was working on vapor flow for the Grids model. We also joked that the challenging part here is creating this “accurately and performatively without single-handedly developing Weather Simulator 2020.” Unfortunately, the joke is all too real!

That doesn’t mean we are actually developing a complex weather simulator, but there is nonetheless complexity. While developing the vapor flow model, Jenn has been doing her homework with research into fluid systems and geophysics (if you’re looking for some light reading, you can check out Lectures On Dynamical Meteorology, Geophysical Fluid Dynamics, and An Introduction to Planetary Atmospheres).

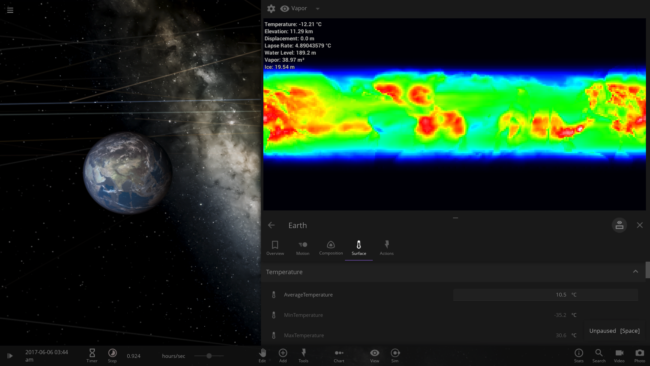

The first part of vapor flow is determining what exactly is vapor; this is done by phase tracking, which determines what phase each material is in, based on temperature and elevation. For water, vapor is its gas state, then we need to see where it’s headed from there — whether it’s evaporating or condensing at the dew point, depositing, if it should be boiling away completely, etc. If it’s remaining as vapor, then the model accounts for a few factors to move it around: there are the prevailing winds which vary by latitude, are affected by planet rotation, and cause east-west movements (as seen in the GIF at the top), and there are temperature differentials from thermal flows and elevation that cause north-south movement (still a work in progress).

Image: The “heat map” shows vapor amounts (not vapor flow), where red is higher amounts and blue is lower. The poles are both much drier, and because there’s much less evaporation over land than oceans, you can see the outlines of the continents.

We want to stress that this is necessarily a very simplistic model, largely limited by its low resolution and the amount of memory we can allocate for this single component of Grids. There are lots of things missing that make this very different from more complex weather simulations — there are no vortices, so there won’t be anything like hurricanes, it is only a 2D simulation with no layers through the vertical dimension, and it’s fairly low resolution.

But we hope to use this data for the resulting local vapor amounts to have rough approximations for clouds, ice caps (for Mars, this effect happens with CO2 vapor flow), and for the future implementation of basic life simulation (vegetation), it could affect growth in dry and wet areas.

Loading…

In our last post, we also mentioned Chris’s work on saving and loading with Grids. This component of the feature obviously isn’t as interesting as, say, lasers, but at the same time, it’s essential to get it right and it’s another good representation of challenges on the edges of new feature development.

Here’s a shortlist of some of the questions and challenges that doesn’t even get into the technical weeds: How can we deal with file type and size limits for different platforms, like Steam Workshop, mobile devices, etc.? How can we maintain file size for fast, background autosaving and quicksaving? How can we get it to play nicely with previously saved simulations with objects that didn’t have all of the Grids data?

We had similar saving and loading questions with the new galaxies: What should happen if you load simulations that had the old galaxies? They won’t look and function the same. Should we change their shape and motion to use the new model, or should we preserve appearance? Is it okay to change sims on Steam Workshop that are very popular?

Saving and loading is something we all hope just works seamlessly and shouldn’t be something the player ever has to think about — which are both telltale signs that there is little room for bugs, errors, and bad user experience (UX). Thankfully, we have answers to all of these questions!

What’s Next for Grids

We’re hoping to make some good progress again on the visual side of Grids, rendering all of that wondrous data into some nice planet graphics. We’ve been recruiting our graphics developer, Georg, to work on some other projects (like the now so gorgeous galaxies), but it’s time for Grids attention again.

Thanks for reading! We’ll be back in two weeks with another update on development. And hopefully before that, we’ll have our next big update with new galaxies.

Dark Matter & Galaxies in Universe Sandbox

Jun 20th

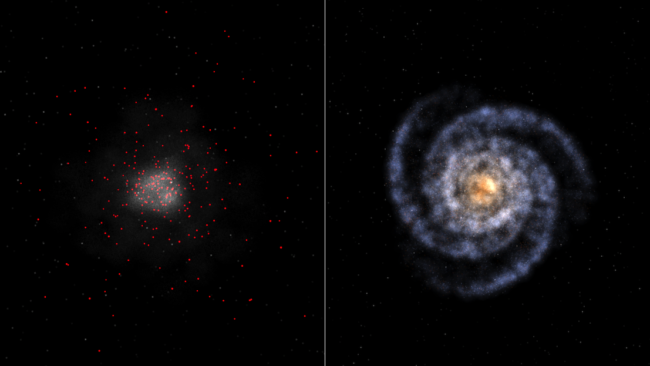

You may notice that our new galaxy model (added in Update 23, released on June 25, 2019) no longer includes those bright red dots. The dots were how we represented dark matter in the old galaxy model (pre-Update 23), but we’ve decided not to include dark matter in the new model, for a number of reasons.

Short Explanation

Here’s the TL;DR explanation of why we removed dark matter in our new galaxy model:

Dark matter is a theoretical particle proposed to explain the unexpected motion of stars in galaxies. Due to performance constraints, our simplified galaxy dynamics model can’t simulate these complex orbits, so we’ve decided to remove dark matter from our simulations for now.

If you’re looking for a more in-depth explanation, keep reading!

Left: Spiral galaxy with dark matter (pre-Update 23). Right: Spiral galaxy in Update 23.

What is dark matter?

No one knows for sure what dark matter is, or even if it exists! But a number of different observations of our universe have revealed stars and galaxies moving under the gravitational influence of more mass than we can see. This hints at the presence of some kind of matter that affects stars and other bodies via gravity, but that can’t be observed directly. This proposed “dark matter” doesn’t produce light, but it also doesn’t block it, or we would be able to see it silhouetted against brighter stars and galaxies in the background (like we can see dust in the Milky Way).

We don’t know of a type of particle that has mass but that doesn’t interact with light, but a few ideas have been proposed. It may be a new type of particle that we haven’t discovered yet, and several ongoing experiments are trying to directly detect such a particle. Some scientists argue that dark matter does not exist at all, and that the “missing mass” in astronomical observations simply indicates that our mathematical description of gravity is not yet complete.

What does this have to do with galaxies?

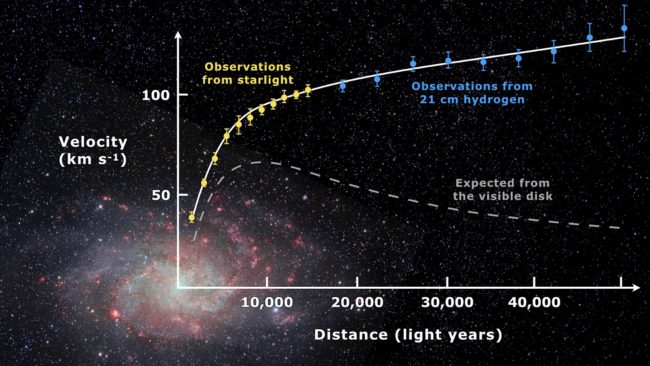

Spiral galaxies were one of the first examples of the missing mass problem. Astronomers discovered the problem while calculating the “rotation curve” for these galaxies: a plot of the velocity of a star orbiting in the galaxy, versus the distance of that star to the center of the galaxy. The speed at which an object orbits in space is related to the mass of everything inside its orbit, and the distance to the center of the orbit. In the Solar System, nearly all of the mass inside a planet’s orbit is made up of the mass of the Sun, so the difference in speeds of planet orbits is due mostly to their distance from the Sun. Thus, the rotation curve of planets in the Solar System starts with the high speed of Mercury’s orbit, and then drops off as you move outwards to Venus, Earth, and the rest of the planets.

But in a galaxy, most of the mass is distributed among the stars that make up the galaxy, so stars farther from the center are orbiting more mass than stars closer in. We can estimate the distribution of mass based on the stars that we see, and predict a slightly more complicated curve: First, the velocities of orbiting stars should increase as you move away from the center, as more and more mass is enclosed by the orbit. But eventually, the extra mass inside the orbit won’t be enough to make up for the increased distance from the center, and the velocities will start to decrease again. The predicted curve has a sort of hump shape, with a long, decreasing tail.

Rotation curve of the galaxy M33. The yellow and blue dots indicate the data, while the dashed line represents the curve you would expect based on the amount of visible mass in the galaxy. Instead, the velocity increases with distance, indicating that more mass is present than we can see. Credit: Mario De Leo

But when astronomers actually measure these velocities and create rotation curves of spiral galaxies, the curves don’t drop off with distance. Instead, the velocities get faster and faster as you move outwards, with stars on the outer edges moving so fast that you would expect them to fly off, pulling the galaxy apart. One explanation for this discrepancy is that some kind of unseen mass (“dark matter”) may be present in spiral galaxies, keeping those stars gravitationally bound to the galaxy despite their high speeds.

Dark matter in Universe Sandbox

Since Universe Sandbox is at its core a gravity simulator, we tried to show the influence of dark matter in our previous galaxy model. For a given galaxy, we would calculate the distribution of dark matter that we would expect based on real observations of galaxy rotation curves. Specifically, we used what’s called the Navarro-Frenk-White (NFW) profile, after the astronomers who identified the distribution. We simulated the dark matter as points of mass scattered through the galaxy, and displayed them as bright red dots (because dark matter is invisible, we wanted to make it clear that we weren’t showing what dark matter “really” looks like!).

This model would give the “right” distribution of dark matter in a galaxy, but it couldn’t reproduce the most important feature of dark matter in galaxies: the rotation curve. This is because of the way that galaxy simulation works in Universe Sandbox.

How galaxies are simulated in Universe Sandbox

In both the old and the new versions of our galaxy model, we represent the galaxy as a collection of non-attracting particles orbiting a single attracting body, the black hole at the center. Each particle represents a cloud of gas, dust, and stars, which we call a nebula. This means that to our physics engine, the nebulae have zero mass, and the only gravity in the galaxy comes from the black hole.

But wait, earlier we said that the mass in a galaxy is spread out among all the stars in the galaxy, instead of being concentrated in the center like the Solar System. Why don’t we make all the nebulae into attracting particles? This would certainly make the motion of the galaxy more accurate, but in any gravity simulator, the number of attracting particles significantly affects performance. (You can see this for yourself by opening a simulation with a lot of attracting bodies, like Earth & 50 Moons.) To make galaxies look as good as they do, we need to use hundreds or even thousands of nebulae. A simulation with a thousand attracting particles would run extremely slowly even on a very powerful gaming computer. So instead, we used a simplified model of non-attracting nebulae orbiting an attracting black hole.

In the old version of galaxies, nebulae moved on circular orbits around the black hole, and the initial structure of a galaxy, whether it was a spiral or elliptical, would quickly lose its distinctive shape. In our upgraded version, nebulae are given specific orbits to allow the galaxy to hold its shape over time. The presence of another attracting body besides the black hole will pull the galaxy out of shape. (You can watch this happen in any galaxy collision simulation, or just by adding multiple galaxies to one of your own simulations!) During the development of this upgrade, we realized that adding attracting particles to represent dark matter would make it difficult to maintain the shape of spiral and elliptical galaxies for the same reason.

Because we are using a simplified galaxy model, we can’t reproduce the galaxy rotation curves we would expect either with or without dark matter. Instead, the rotation curves for our galaxies look more like the Solar System’s: the velocities of the nebulae drop off quickly as you move outwards from the center. Since this model can’t demonstrate the major effect of dark matter in galaxies, we decided to remove it for now.

We are hoping that a future version of galaxies will use computational methods like Smoothed-Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) that will allow us to simulate hundreds to thousands of attracting nebulae orbiting the galaxy. This even more accurate model will be able to produce realistic galaxy rotation curves, and at that point, we’ll add dark matter back in so users can see its observable effect. In the meantime, we hope you enjoy our improved, interactive galaxy model!

Galaxies & Grids | Dev Update #5

Jun 7th

For this developer update, we’re going to take a little break from looking at our work on Surface Grids & Lasers to turn our attention on the upcoming new galaxies (these are a work-in-progress and are not yet available in Universe Sandbox).

You can check out Dev Update #1, Dev Update #2, Dev Update #3, and Dev Update #4 for a more in-depth look at Surface Grids & Lasers.

Keep in mind this is a development log for work-in-progress features. Anything discussed or shown may not be representative of the final release states for these features.

A Whole New World (of Galaxies)

We’ve been saying for a while now — and the community has been making sure to regularly remind us — that the state of galaxies in Universe Sandbox has not been so good. There was a pretty good looking preset simulation for a Milky Way & Andromeda Collision, but when it came to adding any type of galaxy to another simulation, you were left wondering why they all looked like the same amorphous blob, why they were difficult to work with, and what exactly all those red dots were.

Case in point, here’s a Milky Way added to a simulation with the old galaxies:

And here’s a new Milky Way:

We hope you agree this is a massive visual improvement. But there’s more than just beautification happening. Here are the major parts that make up the new galaxies:

1. Black holes & nebulae

- A galaxy is a combination of a black hole and a number of surrounding nebulae (each of which represents a group of stars)

2. Individual, editable properties

- Select and edit properties for black holes, individual nebulae, or the whole galaxy

- Each includes typical object properties like mass, radius, rotation, position, velocity, etc.

- Unique whole galaxy properties include galaxy type (elliptical, spiral, and irregular), elliptical B/A ratio, spiral number of arms, and pitch angle

3. Accurate motion

- Orbital elements of the nebulae are set by galaxy type and determine overall motion

- Nebulae positions and velocities change as galaxy type and type-related properties (B/A ratio, pitch angle, etc) are edited

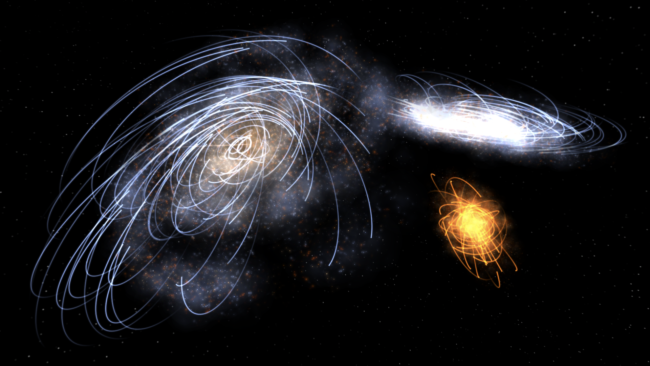

- Galaxies in isolation will retain proper motion and shape over time

- Galaxies perturbed by massive bodies (like another galaxy or an isolated, supermassive black hole) become irregular type galaxies

4. Data-driven visuals

- Nebulae have a Gas Fraction property that represents the ratio of gas (the material available for making stars) to stars as well as an average temperature property

- Combined, these properties result in red/yellow elliptical galaxies, bluer spiral arms, and a visible increase in blue star production in colliding galaxies

- Nebulae also have a Dust Fraction property that represents the ratio of dust (opaque material) to gas and stars (luminous material); dust traces spiral arms and blocks light from the galaxy when viewed edge-on

GIF: Editable properties and the different visuals for different types of galaxies.

5. Procedural generation

- Create a randomly generated spiral galaxy, elliptical galaxy, or irregular galaxy

6. Support for trails & orbits

- Show trails or orbits for individual nebulae, which provides insight into realistic galaxy motion

7. No more dark matter

- Proper dark matter simulation is very complicated and we weren’t satisfied with its implementation in our last galaxy model

- In the future we’ll have a more in-depth explanation of this in a blog post from Erika, Universe Sandbox astrophysicist and developer behind the new galaxies

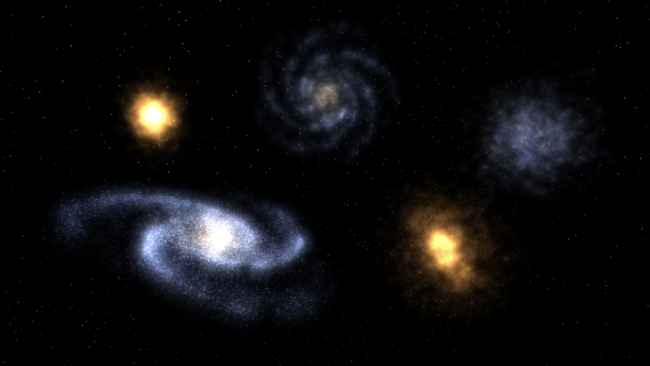

Image: A collection of randomly generated spiral, elliptical, and irregular galaxies.

The Future of Galaxies

We’re very happy with the status of galaxies right now. Before we can release them, there are some minor changes we need to make with the interface and other miscellaneous areas around the edges, and we still need a round or three of testing and bug fixes. But the simulation itself is in great shape.

When it comes to simulation features in Universe Sandbox, though, we almost never consider them a done deal. There are always improvements we have in mind for making them more realistic, performant, and fun to experiment with.

After the initial release of these new galaxies we’ll likely take a break from them for a bit. But here are some improvements and additions we’d love to explore more in the future:

- Barred spiral galaxies

- Visual representation of accurately-timed supernova flashes

- Values to show estimated numbers of stars in nebulae and total values in galaxy groups

- Randomization parameters for more “natural-looking” galaxies

- Run as fluid/SPH (smoothed-particle hydrodynamics) simulation

Surface Grids Sidebar

We’re hyped on galaxies and hope you are, too. Fingers crossed that the last stretch of finishing out this feature goes smoothly and quickly!

But of course, we’re also still working on Surface Grids & Lasers, so here’s a small update on those features:

Chris has been working on the saving and loading system for Surface Grids. This is a little less straightforward than it had been for saving and loading objects and simulations, due to the sheer amount of data that can be included with a lot of objects using the new Grids system.

Jenn has continued with making an accurate water vapor model, with the challenge of creating this accurately and performatively without single-handedly developing Weather Simulator 2020.

Georg has been applying his shader magic to galaxies and helping with proper rendering for Universe Sandbox on Magic Leap. Now that the graphics work for both of those are mostly finished, he’s got his eye on Surface Grids again as he continues to shape water data and heightmaps to get nice looking coastlines on Earth and other planets.

Stay tuned for another announcement about an opt-in version of Universe Sandbox that includes these new galaxies — we need to squash some of the nastier bugs still, but we’re getting close.